A History of Desire

Russian Caviar - The Legend of Sturgeon Caviar

Once reserved only for royalty, caviar has long been considered a "food of the gods." But how did it acquire such a refined reputation in the first place? And what really happened to sturgeon stocks in the Caspian Sea at the end of the Soviet era?

ANCIENT CIVILIZATIONS

Many myths and legends are associated with caviar. According to records from the Greek philosopher Aristotle, caviar and sturgeon were being heralded in to Greek banquets among trumpets and flowers from as early as the fourth century BC.

However it was ancient Persians who created salted caviar. Legend has it that they widely believed it to have medicinal powers, and thus the word caviar comes from the Persian "khav-yar" meaning "cake of power".

Another of the more popular stories suggests that the word caviar is derived from the Persian "khag-viar, which literally translates to "small black eggs".

Whatever the origins of the word, what we know for sure is that fishermen on the Caspian Sea and the Volga began eating caviar, not as a delicacy, but as a basic food. The main reason for this was that caviar quickly spoiled without refridgeration, and it was precisely this perishability that made caviar so exclusive, and therefore fascinating, to the Czars, noblemen and aristocrats of the day.

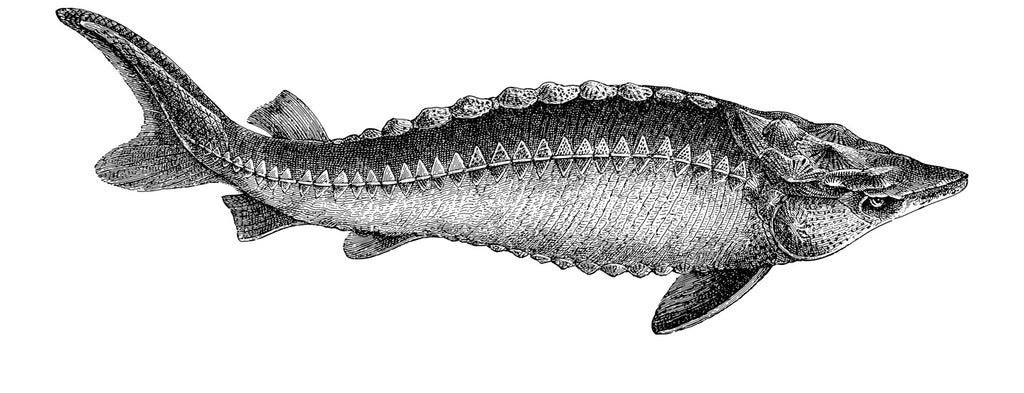

By the Middle Ages, the majestic sturgeon had become much more established among the higher echelons of European society. In 1324, the English king Edward II declared sturgeon to be a "Royal Fish" and only people in the royal court were permitted to eat it. This is a tradition which continues to this day - all wild sturgeon found within the foreshore of the United Kingdom are still decreed the property of the monarch.

When the aristocracy in Russia and Europe started developing a taste for "black gold" in the mid-1800's, the countries bordering the Caspian Sea began to harvest sturgeon in ever greater quantities, which helped boost the popularity of caviar around the world. But increased demand and over-fishing began depleting wild stocks from what was once a healthy sturgeon population.

FROM ROE TO RUIN

After the Russian Revolution in 1917, the Communist party set up a cartel to sell the coveted Caspian Sea caviar to a growing market of affluent Europeans and North Americans who wanted a taste of the delicacy Czars were consuming by the kilo. High end restaurants in Europe started to offer caviar from the Caspian as an appetizer, while North American bar owners served caviar from the Delaware River free-of-charge in the belief that the salty taste encouraged customers to buy more drinks!

As the world became wealthier and more populous, demand for caviar soon outstripped supply. Prices were pushed up and caviar became an expensive luxury for only the wealthiest customers once more.

In the mid-eighties, the dawn of the Russian Federation saw the Caspian caviar industry flourish around the coastal city of Astrakhan. By 1997 though, it became apparent that many species of sturgeon were in deep trouble. Over-fishing, pollution, illegal poaching and the construction of dams preventing sturgeon returning to their spawning grounds all contributed to the decline in wild stocks.

In 1998, countries that were signed up to the UN-administered CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora) programme, immediately brought in export controls on 25 of the world's 27 sturgeon species (trading in the other two species was banned altogether).

THE MODERN ERA

In early 2006, faced with further drops in sturgeon stocks, CITES suspended all imports and exports of wild caviar until producing nations came up with better plans to deal with the crisis.

The UN lifted its export ban on three types of caviar early in 2007, including the highly prized Beluga. A UN-sponsored conservation body reported that countries bordering the Caspian Sea had improved their monitoring of caviar trading, but declared that the resumption of exports must be accompanied by additional moves to combat declining sturgeon stocks.

So as recently as twenty years ago, nearly all the caviar consumed in Europe came from the Caspian Sea where the trade was dominated by a handful of Iranian and Russian caviar traders. However, since the introduction of CITES controls in 1998, and driven by demand from consumers for sustainably produced sturgeon caviar, the industry has grown into a global farming business spanning all seven continents.

All the caviar that is consumed today is farmed – there is no legal caviar on the market from wild sturgeon caught in the Caspian Sea.